|

|

Reply

| |

What Is Depression?  While sadness touches all of our lives at different times, the illness of depression can have enormous depth and staying power. Even the ancient Greeks noted how disabling it could be, and that it was more than a passing bout of sadness or dejection, or feeling down in the dumps. If you have ever suffered from depression or been close to someone who has, you know that this illness cannot be lifted at will or wished or joked away. A man in the grip of depression can’t solve his problems by showing a little more backbone. Nor can a woman who is depressed simply shake off the blues.

Being depressed has nothing to do with personal weakness. Scientists�?developing knowledge of brain chemistry and findings from brain imaging studies reveal that changes in nerve pathways and brain chemicals called neurotransmitters can affect your moods and thoughts. These neurological changes may bubble up as symptoms of depression �?including derailed sleep, suppressed appetite, agitation, exhaustion, or apathy. In addition, genetic studies show that although no single gene prompts depression, a combination of genetic variations may heighten vulnerability to this disease.

Nerve pathways, chemistry, and genetics aren’t the whole story, though. Depression could be described as a lake fed by many streams. Its tributaries include traumatic or stressful life events, such as the death of a loved one, and psychological traits, such as a pessimistic outlook or a tendency toward isolation. An episode of depression may result from one particularly powerful experience or from a confluence of several factors. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, during a given year approximately 1 in 10 adults will suffer from some form of depression. Each episode usually affects a chain of people. It can fray bonds between you and your family and friends by spoiling intimacy, sapping emotional resources, and stealing the joy of shared pleasures.

Thankfully, years of research and breakthroughs have made this serious illness easier to treat. Early recognition of the signs of depression is more common than in the past. Newer treatments, such as drugs targeted at specific changes in brain chemistry, can cut short otherwise crippling episodes. A variety of drugs and therapies can also be combined to boost the likelihood of a full remission.

Just like a rash or heart disease, depression can take many forms. Definitions of depression and the therapies designed to ease this disease’s grip continue to evolve. These shifts will continue to percolate through the field as more research flows in. What Is Major Depression? Major depression may make you feel as though work, school, relationships, and other aspects of your life have been derailed or put on hold indefinitely. You feel constantly sad or burdened, or you lose interest in all activities, even those you previously enjoyed. This holds true nearly all day, on most days, and lasts at least two weeks. During this time, you also experience at least four of the following signs of depression: - a change in appetite that sometimes leads to weight loss or gain

- insomnia or (less often) oversleeping

- a slowdown in talking and performing tasks or, conversely, restlessness and an inability to sit still

- loss of energy or feeling tired much of the time

- problems concentrating or making decisions

- feelings of worthlessness or excessive, inappropriate guilt

- thoughts of death or suicide, or suicide plans or attempts.

Other signs can include a loss of sexual desire, pessimistic or hopeless feelings, and physical symptoms such as headaches, unexplained aches and pains, or digestive problems. Depression and anxiety often occur simultaneously, so you may also feel worried or distressed more often than you used to. Although these symptoms are hallmarks of depression, if you talk to any two depressed people about their experiences, you might well think they were describing entirely different illnesses. For example, one might not be able to summon the energy to leave the house, while the other might feel agitated and restless. One might feel deeply sad and break into tears easily. The other might snap irritably at the least provocation. One might pick at food, while the other might munch constantly. On a subtler level, two people might both report feeling sad, but the quality of their moods could differ substantially in depth and darkness. Also, symptoms may gather over a period of days, weeks, or months. Despite such wide variations, depression does have certain common patterns. For example, women are almost twice as likely as men to suffer from depression. And while major depression may start at any time in life, the initial episode occurs, on average, during the mid-20s. Depression or hopelessness may feel so paralyzing that you find it hard to seek help. Even worse, you may believe that treatment could never overcome the juggernaut bearing down. Yet nothing could be further from the truth. The vast majority of people who receive proper treatment rebound emotionally within two to six weeks and then take pleasure in life once again. When major depression goes untreated, though, suffering can last for months. Furthermore, episodes of depression frequently recur. About half of those who sink into an episode of major depression will have at least one more episode later in life. Some researchers think that diagnosing depression early and treating it successfully can help forestall such recurrences. They suspect that the more episodes of depression you’ve had, the more likely you are to have future episodes, because depression may cause enduring changes in brain circuits and chemicals that affect mood (see The Problem of Recurrence). In addition, people who suffer from recurrent major depression have a higher risk of developing bipolar disorder than people who experience a single episode. What Is Dysthymia? Mental health professionals use the term dysthymia (dis-THIGH-me-ah) to refer to a low-level drone of depression that lasts for at least two years in adults or one year in children and teens. While not as crippling as major depression, its persistent hold can keep you from feeling good and can intrude upon your work, school, and social life. If you were to equate depression with the color black, dysthymia might be likened to a dim gray. Unlike major depression, in which relatively short episodes may be separated by considerable spans of time, dysthymia lasts for an average of at least five years. If you suffer from dysthymia, more often than not you feel depressed during most of the day. You may carry out daily responsibilities, but much of the zest is gone from your life. Your depressed mood doesn’t lift for more than two months at a time, and you also have at least two of the following symptoms: - overeating or loss of appetite

- insomnia or sleeping too much

- tiredness or lack of energy

- low self-esteem

- trouble concentrating or making decisions

- hopelessness.

Sometimes an episode of major depression occurs on top of dysthymia; this is known as double depression. Dysthymia often begins in childhood, the teen years, or early adulthood. Being drawn into this low-level depression appears to make major depression more likely. In fact, up to 75% of people who are diagnosed with dysthymia will have an episode of major depression within five years. It’s difficult to escape the grasp of untreated dysthymia. Only about 10% of people spontaneously emerge from it in a given year. Some appear to get beyond it for as long as two months, only to spiral downward again. However, proper treatment eases dysthymia and other depressive disorders in about four out of five people. What Is Bipolar Disorder? Bipolar disorder always includes one or more episodes of mania, characterized by high mood, grandiose thoughts, and erratic behavior. It also often includes episodes of depression. During a typical manic episode, you would feel terrifically elated, expansive, or irritated over the course of a week or longer. You would also experience at least three of the following symptoms:

- grandiose ideas or pumped-up self-esteem

- far less need for sleep than normal

- an urgent desire to talk

- racing thoughts and distractibility

- increased activity that may be directed to accomplishing a goal or expressed as agitation

- a pleasure-seeking urge that might get funneled into sexual sprees, overspending, or a variety of schemes, often with disastrous consequences.

Between episodes, you might feel completely normal for months or even years. Or you might experience faster mood swings (known as rapid cycling). Bipolar disorder actually takes many forms. For example, symptoms of depression and mania may be mixed during cycles. Or you might not have full-blown mania; instead, you could have a milder version known as hypomania. Bipolar disorder usually starts in early adulthood. It’s equally common among women and men, although certain variations of it strike one sex more than the other. Hypomania, for example, occurs more often in women. Women are also more likely to experience major depression as their first episode and to have more depressive episodes over all. Men, on the other hand, typically experience manic episodes first and tend to have more of them than depressive cycles. Bipolar disorder is a recurring illness. Nine out of 10 people who have a single manic episode can expect to have repeat experiences. Suicide rates in people who have bipolar disorder are higher than average. Successful treatment, however, can cut down on the number and intensity of episodes and reduce suicide risk.

|

|

First First

Previous

2-12 of 12

Next Previous

2-12 of 12

Next Last

Last

|

|

Reply

| |

Who’s at Risk for Depression?  All over the world, depression is much more common in women than in men. In the United States, the ratio is two to one, and depression is the main cause of disability in women. One out of eight women will have an episode of major depression at some time in her life. Women also have higher rates of seasonal affective disorder, depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder, and dysthymia. Why are women so disproportionately affected? Many theories have been advanced to explain this difference. Some experts believe that depression is underreported in men (see Men and Depression). But there may also be other, more complex reasons for women’s greater vulnerability to depression. <v:shapetype id=_x0000_t75 coordsize="21600,21600" o:spt="75" o:preferrelative="t" path="m@4@5l@4@11@9@11@9@5xe" filled="f" stroked="f"><v:stroke join=""></v:stroke><v:formulas><v:f eqn="if lineDrawn pixelLineWidth 0"></v:f><v:f eqn="sum @0 1 0"></v:f><v:f eqn="sum 0 0 @1"></v:f><v:f eqn="prod @2 1 2"></v:f><v:f eqn="prod @3 21600 pixelWidth"></v:f><v:f eqn="prod @3 21600 pixelHeight"></v:f><v:f eqn="sum @0 0 1"></v:f><v:f eqn="prod @6 1 2"></v:f><v:f eqn="prod @7 21600 pixelWidth"></v:f><v:f eqn="sum @8 21600 0"></v:f><v:f eqn="prod @7 21600 pixelHeight"></v:f><v:f eqn="sum @10 21600 0"></v:f></v:formulas><v:path o:extrusionok="f" gradientshapeok="t" o:connecttype="rect"></v:path></v:shapetype><v:shape id=_x0000_i1025><v:imagedata src="file:///C:\DOCUME~1\ehenry\LOCALS~1\Temp\msohtml1\01\clip_image001.jpg" o:title=""></v:imagedata></v:shape> Women Under Stress  A survey of 30,000 people in 30 countries has found that in similar circumstances, women are more likely than men to say they are under stress. Other studies suggest that women are three times more likely than men to become depressed in response to a stressful event. And women are disproportionately subject to certain kinds of severe stress �?especially child sexual abuse, adult sexual assaults, and domestic violence.

Everyday experiences as well as traumatic ones may provoke stress, leading to depression in women. Women, who are often raised to care for others, tend to subordinate their own needs more than men. For example, women who work outside the home also tend to work a "second shift" �?taking care of housework, children, and older relatives. Many have too much to do in too little time, with too little control over how it is done. Marriage and children, while a haven for some women, ratchet up the stress level for others. Studies have found that, compared with their single counterparts or married men, married women are less likely to feel satisfied. In an unhappy marriage, the wife is three times more likely to be depressed than the husband. Being a mother of young children increases your risk for depression, too.

Another kind of stress is poverty. Women are on average poorer than men �?especially single mothers with young children, who have a particularly high rate of depression. The Effect of Hormones  Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) can involve emotional fluctuations on top of physical symptoms such as bloating and tiredness. Women with PMS may feel sad, anxious, irritable, and angry. They may also suffer from crying spells, mood changes, trouble concentrating, loss of interest in daily activities, and a feeling of being overwhelmed or out of control. Sometimes depression is mistaken for PMS, or vice versa. To help distinguish the two, chart your symptoms through two menstrual cycles to see if they appear only in the week before menstruation and go away a day or two after bleeding begins. If a clear and persistent pattern emerges, it’s likely that changing hormone levels are to blame. If a clear pattern doesn’t emerge, depression may be the culprit.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder is a severe form of PMS that occurs in 2%�?0% of menstruating women. It can cause symptoms similar to a major depressive episode in women who are unusually sensitive to the changing hormone levels of the menstrual cycle. Some of that sensitivity may be due to interactions between female hormones and neurotransmitters that regulate mood and arousal.

Whether PMS, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, or depression is at the root of your symptoms, it’s important to talk to your doctor about the fluctuations in your mood and how best to treat them.

Researchers are also investigating whether hormones play a role in depression around the time of menopause. Some women report feeling depressed during perimenopause, a time of transition that occurs in the months or years before menstruation stops. It’s commonly believed that declining levels of estrogen are to blame, although this has not been proved scientifically. When estrogen is given to treat depression, the results have been mixed. For now, estrogen’s role in depression during perimenopause remains controversial. Genes

There is evidence to suggest that genes play a role, too. Researchers have identified certain genetic mutations that are linked to severe depression �?some of which are found only in women. In one of these cases, the mutation is in a gene that controls female hormone regulation. These biological differences could account for some of the difference in the rates of depression between men and women. Expectant and New Mothers  During pregnancy, women should be cautious about taking any type of medication. But the risks of not taking a needed medication should be weighed against the possible risks (to both mother and baby) of taking the drug. Drugs to treat depression are no exception. Mothers-to-be who are depressed may have a hard time caring for themselves. They are more likely to miss doctors�?appointments and to drink alcohol or use drugs. Their children may end up having lower birth weights and associated health problems. And of course, depression can sometimes be fatal through suicide. When depression is severe, pregnant women may find that the benefits of treatment far outweigh the risks. The understanding of how antidepressant medications affect the babies of mothers who take these drugs during pregnancy is still evolving. In 2005 and 2006, studies showed a higher risk of relatively rare birth defects in babies whose mothers took SSRI medications during pregnancy. And some newborns develop withdrawal symptoms like abnormal crying and irritability as the medication leaves their system. Mood stabilizers, including lithium (Eskalith, Lithonate) and carbamazepine (Tegretol), also have been linked to a higher risk of birth defects. In general, the risks to the babies are small. In every case, a woman should discuss with her doctor the advantages and disadvantages of taking (or stopping) any depression or mood-stabilizing drugs during pregnancy. Studies have found that antidepressants don’t pose a serious risk to nursing infants. As a safeguard, though, nursing women might opt for drugs that don’t accumulate in breast milk, such as sertraline (Zoloft). Some pregnant or breast-feeding women prefer to err on the safe side and avoid medication. In addition to psychotherapy (and ECT in severe cases), these women can try phototherapy, which uses bright artificial light to help lift depression (see Seasonal Affective Disorder). This has been shown to help some people out of depression, including pregnant women. Postpartum Depression More than half of women who’ve recently had a baby endure the weepy, anxious, emotional time known as the "baby blues." Yet, unlike the baby blues, which usually last no more than a few weeks, postpartum depression continues and deepens. About 10%�?5% of new mothers experience depression within three to six months after childbirth. Coming at a time that culture dictates should be happy and fulfilling, this type of depression can carry a stigma that makes some women reluctant to admit to it. Sleep deprivation, the dramatic changes and stresses that accompany motherhood, and shifts in hormones all seem to have a hand in postpartum depression. Physical discomfort, a colicky or sick baby, financial hardship, and scant social support may also be factors. Postpartum depression has many features in common with major depression. A new mother can become sad or hopeless. She may be anxious and especially worried about the baby’s well-being. She may not be able to function and may be overwhelmed by caring for her baby. She may experience changes in appetite that lead to weight loss or gain. She may also lose interest in everything, including the baby, and feel guilty or worthless as a result. If you suffer postpartum depression, treatments (including medications and psychotherapy) can make a big difference for both you and your baby (see Treatment for Depression: Getting Help). Men and Depression Although there is considerable evidence that women are twice as likely as men to become depressed, some researchers question this statistic. They contend that if studies accounted for differences in how men and women express and cope with their emotions, this apparent gap in depression rates would diminish or possibly disappear.

Typically, men are more likely to shy away from talking about their feelings, and doctors may bring up emotional topics less often with men. In addition, many men don’t feel comfortable acknowledging the need for help, making them less likely to seek assistance than women are. Men also tend to describe the experience of depression in less intense ways than women do.

Depression in men may be obscured behind a variety of physical complaints, such as low energy, aches and pains, a loss of appetite, or trouble sleeping. Or the problem may come out as substance abuse, anger, or belligerent behavior. Even if other symptoms of depression are present, some men may not feel sad. And if a loved one raises the subject, they may not be willing to admit the possibility that they are depressed. Yet when such men receive treatment for depression, their symptoms often disappear, and in retrospect they may concede that they were, in fact, depressed. Men Have Hormones, Too Some researchers have examined whether fluctuations in testosterone levels may promote depression. Later-life changes in sex hormones are not as clear-cut in men as they are in women, but testosterone levels do decrease gradually as men age (a change that is sometimes dubbed "male menopause"). A quarter to a half of men over 50 have testosterone levels that can be considered abnormally low. The problem is more likely to arise if they drink excessively or if they are overweight or under stress (either physical or psychological).

Physicians still have a lot to learn about this subject, but it’s possible to offer a few guidelines. Any man in middle age or older who notices mild to moderate depressive symptoms for the first time may have a problem with low testosterone. A physician can check his testosterone levels, along with pituitary hormone levels and liver and thyroid function. If testosterone is low, it may be worthwhile for him to take a supplement, along with psychotherapy, an antidepressant drug, or both. The more severe the depression, the less likely it is to be related to testosterone deficiency, since low testosterone levels are not closely associated with major depression.

Bringing testosterone levels back into the normal range is relatively safe, but long-term treatment is not without its problems. Testosterone supplements can increase the risk of prostate cancer, spur benign prostate enlargement, and (by boosting the concentration of LDL or "bad" cholesterol) promote heart disease. Liver damage can also occur. Some men develop gynecomastia (breast swelling), headaches, rashes at the site of application, acne, baldness, or emotional instability. Long-term treatment may suppress natural testosterone production, creating problems if the supplement is abruptly withdrawn.

It’s reasonable for older men to consider testosterone as a treatment for depressive symptoms, but only after a full endocrine or hormone evaluation has been done. Because of the many potential side effects, you should begin testosterone therapy only after careful consideration and an in-depth discussion with your doctor. Work and relationships

In this culture, male self-esteem often depends on success at work, physical skill or power, and being physically or mentally active. If a man’s capacity in any of those areas is diminished �?especially if he loses a job or his marriage fails �?it may help trigger depression.

Depression is so common that it should be considered as much a problem for men as it is for women. In fact, men are more at risk for the worst outcome of depression �?suicide. Family members, friends, and caregivers may need to meet them more than halfway to see that they get the help they need (see How to Cope When a Loved One Is Depressed, Suicidal, or Manic). Children and Teenagers  While some people idealize childhood, in reality, children may feel shaken by developmental changes and events over which they have little or no control. Studies show that 2 out of every 100 children and 8 in 100 adolescents have major depression. While a full-blown depression most often starts in adulthood, low-grade depression, or dysthymia, may begin during childhood or the teenage years. Although an adult has to have depressive symptoms for at least two years before he or she is diagnosed with dysthymia, in children and teens a diagnosis is made after one year. When dysthymia appears before age 21, major depressive episodes are more likely to emerge later in life. In teens, as in adults, bipolar disorder and depression are clearly connected. As many as 30% of teenagers who experience an episode of major depression develop bipolar disorder in their late teens or early 20s. While rare in early childhood, this disorder occasionally appears in adolescence, especially in cases where a family history of depression exists. Bipolar disorder that emerges during puberty often displays a mixture of high and low symptoms or rapid cycles of highs and lows. Red Flags for Teenage Depression and Mania If you are a parent of a teenager, a list of depressive symptoms may make the hairs on the back of your neck rise. Storminess, apparent exhaustion, apathy, irritability, and rapid-fire changes in every realm, including appetite and sleep habits, are common in adolescents. You might find yourself wondering whether a sudden loss of interest in the clarinet signals depression or merely that your teen now thinks that playing in the school band is uncool. Staying up late and sleeping until noon or throwing over one interest in favor of others probably doesn’t signal depression. But constant exhaustion and an unexplained withdrawal from friends and activities a child once enjoyed are reason for concern. Because depression in children and teens often coexists with behavioral problems, anxiety, or substance abuse, experts consider a wide range of potential indicators, such as these: - poor performance in school or frequent absences

- efforts or threats to run away from home

- bursts of unexplained irritability, shouting, or crying

- markedly increasing hostility or anger

- abuse of alcohol, drugs, or other dangerous substances

- social isolation or loss of interest in friends

- hypersensitivity to rejection or failure

- reckless behavior.

Young children may express feelings of depression as vague physical ailments, such as persistent stomachaches, headaches, and tiredness. Although they may truly be sad, depressed children and teens are more likely to appear irritable. Depressed children don’t oversleep or act sluggish as often as depressed adults do, but otherwise, the symptoms of depressive disorders in children, teenagers, and adults are generally similar (see Symptoms of Depression). Discuss any of the red flags listed above with your child. If you’re still concerned, speaking with your child’s pediatrician or guidance counselor may help. If a family history of bipolar disorder exists, be especially vigilant about watching for manic symptoms. The signs of manic behavior are similar in adults and children (see What Is Bipolar Disorder?). However, teens who are in a manic episode may also: - talk very fast

- be very easily distracted

- get much less sleep than usual, but seem to have the same amount of energy or even more

- have extreme mood changes, for example, shifting between irritability, anger, extreme silliness, or high spirits

- indulge in, think about, or describe hypersexual behavior.

If you notice these symptoms, your child’s pediatrician can help you decide whether to seek professional help. Treating Depression in Teens and Children Just like depressed adults, depressed children and teens need to get help, and the two main methods of treatment are psychotherapy and medication. But there are distinct differences between treating adults and children in most medical fields, and psychiatry is no exception.

Although many studies have shown antidepressant medications to be effective in teens and children, these drugs can also have some dangerous, unintended side effects in a small number of teens. A review by the FDA found that the average risk of suicidal thoughts in depressed teens and children who are taking an antidepressant was 4%, twice the placebo risk of 2%. As discussed in the section Can Antidepressants Trigger Suicide?, the FDA responded to these concerns in 2004 by requiring that drug manufacturers place a "black box" warning about these risks on the package inserts that come with antidepressants.

What does this mean for your depressed child or teen? Of course, treatment decisions should be made (with your input) by a qualified psychiatrist, preferably one who is trained to care for children. Many experts believe that antidepressants play an important role in treating depression in children and teens �?but they must be used with caution. They shouldn’t be viewed as harmless pills to be prescribed flippantly; nor should they be deemed a dangerous therapy that should be reserved as a last resort. If your child needs an antidepressant, the best way to prevent a dangerous outcome is to pay close attention to how he or she is thinking and feeling. Monitor him or her for suicidal thoughts or tendencies, especially in the first few months of treatment, when the risk is thought to be the greatest. Dealing with suicidal remarks

Children and teenagers are by nature more impulsive than adults, their emotions less tempered by experience. Research suggests that regions of the brain that govern judgment do not develop completely until later in life. All too often in this age group, suicidal thoughts translate into action. Never ignore or brush off comments about suicide or even such sweeping, dramatic statements as "I wish I was dead" or "I wish I’d never been born." Instead, follow through by talking to your child about them.

Perhaps these sentiments reflect nothing more than an isolated, angry outburst or hyperbole in the middle of an argument. But you can say, "Tell me what you’ve been thinking" or "Are you telling me about your frustration, or do you really feel like ending your life?" If the answers raise any concerns, if your child always refuses to engage in the conversation, or if he or she seems to exhibit signs of depression or mania, call his or her pediatrician for advice. Older Adults and Depression  Depression is not a normal part of aging, although many older people and their caregivers think the two go hand in hand. As people age, they do often encounter many familiar sources of depression, including losing loved ones and facing health problems. Still, depression can and should be treated in people of all ages.

About 15% of adults over age 65 have significant depressive symptoms, and about 3% have major depression. But, as noted earlier, the risk of suicide increases with age: The National Institute of Mental Health reports that older Americans are disproportionately likely to die by suicide, and that white men over age 85 have the highest suicide rates in the United States. Two studies further underscore why older people with even minor depressive symptoms need treatment: One, published in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology in 2002, found that older adults with signs of depression had diminished immune responses, which may affect their ability to fight off infections or disease. Another, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry in 2004, found that more depressive symptoms in older adults meant more limitations on daily activity and a greater need for care. People with no depressive symptoms received three hours a week of care on average, those with one to three depressive symptoms had about four hours of care a week, and those with four to eight depressive symptoms needed six hours of care a week.

Research has also linked depression to cancer and Alzheimer’s disease in older people. A long-term study of more than 4,800 men and women over age 70, reported in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, found that those who suffered from chronic depression lasting at least six years had an 88% higher risk of developing cancer. In another study, Dutch researchers followed several thousand seniors over the course of three years. They noted that the risk of developing Alzheimer’s or experiencing a decline in mental powers was higher among those who were depressed. Treating Depression in the Elderly Although roadblocks to treatment exist for most individuals with depression (see Overcoming Barriers to Treatment), an older adult’s road to recovery can seem especially difficult. For example, in older people, depression is sometimes mistaken for dementia (see Is It Dementia or Depression?). Or it may occur in conjunction with dementia or other illnesses that mask the depressive symptoms. Health care professionals may treat the medical illness and overlook the depression. In addition, many in this older generation mistakenly regard depression as a weakness or a shameful family secret. In fact, older people are least likely to seek help for depression. Those who do seek help may need to pay for it out of pocket or bridge a wide gap between the costs and what Medicare will cover. Once an older person seeks treatment, other problems may arise. For example, older adults are sometimes more sensitive to side effects of antidepressants. These drugs also may not mix well with medication they take for other illnesses. For these reasons, as many as 40% of older people taking antidepressants quit or repeatedly miss doses because of side effects, memory problems, or difficulty keeping track of complicated drug regimens. Although older patients with severe depression appear to respond to antidepressant drugs about as well as younger people, they sometimes improve more slowly and relapse sooner. However, a knowledgeable doctor can help see you through these kinds of concerns. Psychotherapy alone may help older patients with milder depression, while combining psychotherapy with medication may be helpful for those with more severe depression. Older adults in good physical and cognitive health may respond well to cognitive behavioral therapy or interpersonal therapy (see Types of Psychotherapy). Cognitive behavioral therapy has also shown promise among the cognitively impaired and physically ill. |

|

Reply

| |

Symptoms of Depression Identifying your symptoms can be a useful first step toward gaining a deeper understanding of how depression, dysthymia, or bipolar disorder affects you. It may help you open a discussion with a doctor or therapist, too. Be aware, however, that self-tests like this one cannot diagnose depression or any other mental illness. Even if they could, it’s easy to dismiss or overlook symptoms in yourself. It may help to have a friend or relative go over this checklist with you. Also, remember that your feelings count far more than the number of check marks you make. If you think you are depressed or if you have other concerns or questions after taking this test, talk with your doctor or therapist. Depression Checklist Start by checking off any symptoms of depression that you have had for two weeks or longer, or that you’ve noticed in the family member or friend you’re concerned about. Focus on symptoms that have been present almost every day for most of the day. Then look at the key below. (The exception is the item regarding thoughts of suicide or suicide attempts. A check mark warrants an immediate call to a doctor.) - I feel sad or irritable.

- I have lost interest in activities I used to enjoy.

- I’m eating much less than I usually do and have lost weight, or I’m eating much more than I usually do and have gained weight.

- I am sleeping much less or more than I usually do.

- I have no energy or feel tired much of the time.

- I feel anxious and can’t seem to sit still.

- I feel guilty or worthless.

- I have trouble concentrating or find it hard to make decisions.

- I have recurring thoughts about death or suicide, I have a suicide plan, or I have tried to commit suicide.

Scoring Key Depression and dysthymia. If you checked a total of five or more statements on the depression checklist, including at least one of the first two statements, you (or your loved one) may be suffering from an episode of major depression. If you checked fewer statements, including at least one of the first two statements, you may be suffering from a milder form of depression or dysthymia. Manic Episode Checklist Check off any symptoms you’ve noticed for a week or longer in yourself or the person you’re concerned about. Focus on symptoms that are present almost every day during most of the day. - I feel extremely elated, uninhibited, or irritable.

- I have ideas or plans that will have a big impact on myself or on others.

- I have a continuous stream of thoughts racing through my brain.

- I am sleeping far less than I normally do.

- I am talking far more than I normally do.

- I feel quite distracted and find it hard to focus.

- I am energetically pursuing my goals, or I feel agitated and unable to sit still.

- I am actively pursuing pleasures that may have negative consequences, such as buying whatever I want or entering into sexual liaisons or business schemes.

Scoring Key

Manic episode. Checking off four statements on the manic episode checklist, including the first statement, suggests possible bipolar disorder. Note that hypomanic symptoms (milder manic symptoms) may last for as little as four days, not a full week or longer. Mild, Moderate, or Severe Depression? Experts judge the severity of depression by assessing the number of symptoms and the degree to which they impair your life.

Mild: You have some symptoms and find it takes more effort than usual to accomplish what you need to do.

Moderate: You have many symptoms and find they often keep you from accomplishing what you need to do.

Severe: You have nearly all the symptoms and find they almost always keep you from accomplishing daily tasks. Is It Dementia or Depression? In older adults who experience an intellectual decline, it’s sometimes difficult to tell whether the cause is dementia or depression. Both disorders are common in later years, and each can lead to the other. It’s not rare for a person with dementia to become depressed, and a depressed person may lose mental sharpness. The latter case is sometimes called the dementia syndrome of depression. People with this form of depression are often forgetful, move slowly, and have low motivation as well as mental slowing. They may or may not appear depressed. This syndrome responds well to treatments for depression. As mood improves, the person’s energy, ability to concentrate, and intellectual functioning usually return to their previous levels. Although depression and dementia share certain traits, there are some differences that help distinguish one from the other: - Decline in mental functioning tends to be more rapid with depression than with Alzheimer’s or another type of dementia.

- Unlike Alzheimer’s patients, people who are depressed are usually not disoriented.

- People with depression have difficulty concentrating, whereas those affected by Alzheimer’s have problems with short-term memory.

- Writing, speaking, and motor skills aren’t usually impaired in depression.

- Depressed people are more likely to notice and comment on their memory problems, while Alzheimer’s patients may seem indifferent to such changes.

Because there’s no test that can reveal whether someone has depression or dementia, if you and your doctor aren’t certain, it’s worth trying a depression treatment. If depression is at the root, treatment can produce dramatic improvement. Is Pain a Symptom of Depression or a Cause? Pain is depressing, and depression causes and intensifies pain. People with chronic pain have three times the average risk of developing psychiatric symptoms �?usually mood or anxiety disorders �?and depressed patients have three times the average risk of developing chronic pain. When low energy, insomnia, and hopelessness resulting from depression or anxiety perpetuate and aggravate physical pain, it can be impossible to tell which came first or where one leaves off and the other begins.

Pain slows recovery from depression, and depression makes pain more difficult to treat. For example, depression may cause patients to drop out of pain rehabilitation programs. So it often makes sense to treat both pain and depression; that way they are more likely to recede together. Brain pathways

Normally, the brain diverts signals of physical discomfort so that we can concentrate on the external world. When this shutoff mechanism is impaired, physical sensations like pain are more likely to become the center of attention. Brain pathways that handle pain signals use some of the same chemical messengers (neurotransmitters) that are involved in the regulation of mood. (See Nerve Cell Communication for more information.)

When these pathways start to malfunction, pain is intensified, along with sadness, hopelessness, and anxiety. And as chronic pain, like chronic depression, takes root in the nervous system, the problem perpetuates itself. The mysterious disorder known as fibromyalgia may be an example of this kind of biological process linking pain and depression. Its symptoms include widespread muscle pain and tenderness at certain pressure points, with no evidence of tissue damage. Brain scans of people with fibromyalgia show highly active pain centers, and the disorder is more closely associated with depression than most other medical conditions. This leads some experts to speculate that the pain sensitivity and emotional storminess of fibromyalgia result from faulty brain pathways. Treating pain and depression in combination

In pain rehabilitation centers, specialists treat both problems together, often with the same techniques, including progressive muscle relaxation, hypnosis, and meditation. Physicians prescribe standard pain medications �?acetaminophen, aspirin, ibuprofen, and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and in severe cases, opiates �?along with a variety of psychiatric drugs. Almost every drug used in psychiatry can serve as a pain medication (see Medications Used for Depression). By relieving anxiety, fatigue, or insomnia, these medications also ease any related pain. In addition, antidepressants �?sometimes given in low doses �?may relieve pain in ways unrelated to their antidepressant effects.

Exercise and psychotherapy are commonly used at pain centers, too. Physical therapists help patients perform exercises not only to break the vicious cycle of pain and immobility, but also to help relieve depression. Cognitive and behavioral therapies teach pain patients how to avoid fearful anticipation, banish discouraging thoughts, and adjust everyday routines to ward off physical and emotional suffering. Psychotherapy helps demoralized patients and their families tell their stories and describe the experience of pain in its relation to other problems in their lives. |

|

Reply

| |

How Is Depression Diagnosed? Although depression is by no means a silent disease, it is seriously underdiagnosed. Experts estimate that only 34% of people with depression seek help, and only one-third of those who have major depression get the help they need. When people do reach out for help, doctors typically diagnose depression by asking about feelings and experiences. They may also use screening tools and look for possible medical causes by performing a physical exam and sometimes ordering lab tests. A physical exam and medical history may offer clues that point to depression caused by medication or an underlying illness. In these cases, blood tests or x-rays may confirm the problem. Often, when people are unable or unwilling to recognize their own depression, their initial complaints are medical. Headaches, stomach problems, sexual difficulties, and lack of energy are among the more common medical complaints. If your symptoms suggest depression and medical causes seem unlikely, your doctor will be interested in hearing whether you’ve had any feelings of sadness or hopelessness and whether you’ve noticed any changes in your appetite, sex drive, or sleep patterns. He or she may also ask these questions: - Have you or anyone in your family ever suffered from depression or another mental disorder? If so, how was it treated?

- Do you get satisfaction and pleasure from your life?

- Do you ever have thoughts about suicide or have you attempted suicide?

- Do you drink alcohol? If so, how often and how much?

- Do you use any drugs such as marijuana, cocaine, crack, or heroin to get high or relax? If so, which drugs and how often?

Screening Tools To help identify depression, doctors may use such screening tools as these: - Self-report scales, which present you with a checklist of symptoms to fill out. These scales may pick up some symptoms or subtle mood changes that otherwise might not be identified.

- Scales completed by a clinician, which are slightly better at detecting depression than self-reports.

- An interview by a doctor or therapist.

Because you may minimize symptoms or may not even be aware of them, your doctor or therapist may want to speak to someone close to you. Where a child or teen is concerned, the doctor may interview parents and, when possible, teachers or a guidance counselor. When Other Tests May Be Useful There is no lab test to determine whether you have a "chemical imbalance" in the brain. Doctors who want to determine whether someone is depressed generally order tests only when they note a potential health problem during a physical exam or medical history. Most doctors do not embark on a battery of lab tests for many reasons. Tests can be costly and may not be covered by insurance. In some cases, results point the doctor in the wrong direction, leading to more tests and unnecessary anxiety. Usually, self-reports of symptoms combined with the clinical skills of a doctor or therapist are enough to begin treatment of depression or bipolar disorder. Sometimes, however, you may need more tests to confirm a diagnosis, tease out information, or distinguish depression from other psychological or neurological problems. Your doctor may ask you to take any of the following: - Psychological tests, during which you answer questions, respond to pictures, or perform tasks like sorting cards or drawing pictures. These tests can give your doctor a better sense of your coping mechanisms, your temperament, or your ability to organize and plan.

- Tests that look at the brain, such as an EEG or MRI, which can help identify causes of dementia or some rare causes of depression. Both tests are painless. During an EEG, electrodes taped to your scalp pick up electrical signals. An MRI uses magnets, a radio wave transmitter, and a computer to pick up small changes in energy in hydrogen molecules in your brain and process the data to make a detailed scan of your brain.

- Tests for biological causes of depression, such as a blood test to check thyroid function.

Advances in Brain Imaging Not all that long ago, the brain could be viewed only during an autopsy or neurosurgery. Fortunately, newer technology offers a variety of noninvasive ways to study the living, working brain. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), for example, generates a colorful, three-dimensional computer image that accurately depicts structures in the brain. A variant of this brain scan, called functional MRI (fMRI), tracks swift, small metabolic changes that take place when a region of the brain responds during various tasks. For example, fMRI can show the expansion of blood vessels and changes in temperature that typically occur in the brain when a person exercises. Other types of brain scans, such as positron emission tomography (PET) or single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), also track brain activity. PET can zero in on the metabolism of blood sugar, which is an indicator of brain activity. PET and SPECT can map the brain in other ways as well �?for example, by measuring the distribution and density of neurotransmitter receptors in certain areas. Another method, called quantitative electroencephalography, takes things a step further. As with a conventional electroencephalogram (EEG), electrodes placed on the scalp measure electrical activity. But during a quantitative EEG, researchers also calculate values that correlate with activity in specific regions of the brain, allowing scientists to map the brain’s structure and activity. For example, this technology can be used to see what parts of the brain respond when a patient takes a drug. Brain imaging enables investigators to research: - which regions of the brain respond to various tasks or stimuli

- how activity in certain areas of the brain or the size of specific brain structures correlates with depression or other mental illnesses

- how various treatments affect neurotransmitter activity and distribution

- how treatments affect certain biological markers of depression.

One fMRI study published in the Journal of Neuroscience found that the hippocampi of 24 women who had a history of depression were 9%�?3% smaller than those of women who did not. The more bouts of depression a woman had, the smaller the hippocampus. Other brain-scan research has found that depressed people generally have less activity in the prefrontal cortex, a region of the brain vital to judgment and planning. Ultimately, these sophisticated methods may reveal how nerve pathways work and interact, helping define the roles of specific neurotransmitters in mood disorders. By showing how the brain responds to medications and other forms of therapy, new imaging techniques might help improve treatment. |

|

Reply

| |

Treatment for Depression: Getting Help  Asking for help may seem like the hardest task in the world, especially if you feel exhausted and hopeless. Yet that’s just what you need to do if you have symptoms of depression or mania. Even if your symptoms are more vague or you don’t know exactly what the problem is, you may still benefit from a doctor’s opinion and evaluation. If you feel lost or stuck, or are concerned about a feeling, thought, behavior, or situation, seek help. The first step is often the hardest. Talk with your doctor about your problems, or get a referral to a mental health professional from your doctor, a friend, or one of the organizations listed in this report (see Resources). If you are in a crisis or feel suicidal, immediately call 1-800-SUICIDE for advice or go to your local emergency room. Together, you and your doctor or therapist can decide on a treatment plan to alleviate your distress. In addition, the following practical suggestions may help you navigate safely through this difficult time: - Ask a friend or family member to accompany you to your first appointment to help describe your problem, assist you in getting treatment, or simply offer support.

- Take medications as directed. Don’t skip pills or change doses without consulting your doctor. Also, report any side effects right away, and if necessary, talk to your doctor about adjusting your treatment plan.

- Set realistic goals for yourself. Try not to take on more than you can handle.

- Join in activities, and try not to isolate yourself from others. Depending on your personal preferences, attending religious services, having a meal with an understanding friend, or going to a movie, ball game, or concert may help lift your mood.

- Try to exercise regularly or take a daily walk.

- Hold off on making big decisions �?about moving, changing jobs, getting married, or seeking a divorce �?until your depression has eased or is under control.

- If you decide to try a "natural" remedy, such as St. John’s wort, ask your doctor or pharmacist whether it might interact with any other medication you’re taking.

- Friends and family often want to help. Let them.

Treating Depression If we were all carbon copies of one another, identifying the causes of depression and its proper treatment would be simpler. But unique differences in life experience, temperament, and biology make treatment a complex matter. No single treatment works for everyone. However, research suggests that many people benefit from a combination of medication and therapy (see Drugs and Therapy: A Winning Combination?). Often, treatment is divided into three phases. Keep in mind, though, that there are no sharp lines dividing the phases, and very few people take a straight path through them. - In the acute phase, the aim is to relieve your symptoms. Generally, this occurs within 6�?2 weeks, but it may take longer depending on your response to the first treatments you try.

- In the continuation phase, you work with your doctor to maximize your improvements. Further treatment adjustments, such as modifying dosage of a medication, can help. This period takes another four to five months.

- In the maintenance phase, the aim is to prevent relapse. Ongoing treatment is often necessary, especially if you have already experienced several depressive episodes, have chronic low mood, or have risk factors that make a recurrence more likely.

Who Should You See for Treatment? On your road to treatment, your primary care doctor may be your first stop. A good primary care doctor can assess your symptoms with an eye to whether you have any underlying medical problems. If your doctor believes that depression is the main problem, he or she may suggest an antidepressant. Sometimes the initial response to the medication is good. If so, you may not need to go further. However, if you don’t respond well to the first medication, your doctor may refer you to a mental health professional, such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, or psychiatric nurse. Most primary care doctors aren’t equipped to do a more detailed review of the mood problem or to take treatment further with psychotherapy or different medications. You can also find a mental health professional through a local clinic or hospital or through recommendations from family members or friends. While some insurance plans leave the choice of therapist up to you, others limit you to professionals enrolled in their networks. Therefore, it’s worthwhile to check with your insurer before choosing a doctor. Since states have different requirements about who may hang out a shingle as a therapist, inquire about the therapist’s training, and opt only for one who has been formally trained and certified (see 10 Questions to Ask When Choosing a Therapist). Some people like to meet with a few therapists before making the commitment to work with one. Even the most highly recommended person may not be the right match for you. Beginning therapy can be uncomfortable, but if a therapist’s demeanor or office set-up puts you off, you needn’t waste your time trying to make the situation work. Drugs and Therapy: A Winning Combination? No single treatment �?whether a drug or a style of therapy �?can beat depression in every case. But would you be better off with a combination of drugs and therapy? Research suggests the answer is yes.

A review of several studies considered data collected on nearly 600 people treated for major depression. The investigators found recovery was quicker and more likely to occur with interpersonal therapy plus an antidepressant compared with interpersonal or cognitive behavioral therapy alone. A study of more than 400 teens with major depression found similar results: Treatment with the antidepressant fluoxetine along with cognitive behavioral therapy worked better than either treatment alone.

Combination therapy may also help ward off recurrences. A three-year study reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association tracked recurrences of major depression in about 200 people ages 60 or older. Of those who received monthly interpersonal therapy and the medication nortriptyline, 80% avoided a recurrence. In contrast, only 57% of those who received the drug alone, 36% of those given just therapy, and a mere 10% in the placebo group did as well.

A study published in the Archives of General Psychiatry in 2004 found that one reason therapy and medication may complement each other is that they have effects on different parts of the brain.

However, if your depression is mild, research suggests that a combination of drugs and therapy is no better than cognitive behavioral therapy or interpersonal therapy alone.

Of course, it always makes sense to mull over all of your options. If one type of treatment alone isn’t helping you, consider trying combination treatment. What You Should Know About Medications Often, medications are the first choice in treatment, especially if you’re experiencing a severe depression or suicidal urges. Controlled studies have found that about 65%�?5% of people get some relief from antidepressants, compared with 25%�?0% of people taking a placebo (a pill with no biologically active ingredient). But the very same drug that works wonders for a friend may fail to ease your symptoms. You may need to try a few different medications to find the one that works best for you with as few side effects as possible. In some cases, a doctor may prescribe a combination of antidepressants or an antidepressant along with a drug to treat anxiety or distorted thinking. A drug combination may be more effective than either drug alone.

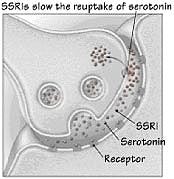

Doctors usually first prescribe medications from a class of drugs known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). SSRIs include fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil), and sertraline (Zoloft). Although the side effects of each drug vary slightly from person to person, you have an equal chance of success on any of these drugs. If you don’t have a good response to the first drug you try, you and your doctor may decide to switch to another. Improvement may take time

Although in a few cases people report a change for the better as quickly as one or two weeks after beginning medication, more often it takes from two to six weeks for antidepressants to ease depression. The lag may reflect the time it takes the medications to affect processes inside the nerve cells and in brain circuits. It’s frustrating but true that side effects may appear before the benefits of a drug become obvious. Once you start to feel better, though, it’s important to take the medication for as long as it’s prescribed to get a full response and avoid a relapse.

While you are using medications, the doctor prescribing them should regularly monitor the dosage and your response. All medical treatments have advantages and disadvantages, and a doctor cannot predict an individual’s response to a given medication. While there’s a good chance that an antidepressant will relieve your symptoms, there’s also a possibility that you’ll encounter side effects. So when you’re about to embark on treatment, it’s important to weigh the potential benefits against the risks. Thankfully, most side effects can be managed or reversed.

Poor response to an antidepressant is often due to an inadequate dose. If the medication doesn’t seem to be working during the first phase of your treatment, don’t be surprised if your doctor suggests increasing the prescribed amount.

Not everyone who takes a drug will be bothered by side effects. If you do experience some, the first step is to report them to your doctor. Your doctor may be able to suggest simple, helpful adjustments (see Managing Side Effects). Many side effects disappear once your body becomes accustomed to the medication. Or, if necessary, you can try a different dosage or drug.

Antidepressants are not habit-forming or addictive. However, if you are about to stop taking these medications, your body needs to readjust slowly, so your doctor may instruct you to reduce the dosage gradually. Even if you do this, you may experience uncomfortable or disturbing symptoms. Sometimes these symptoms are mistaken for a recurrence of the illness (see Preventing a Relapse).

While many antidepressants can be safely combined, some cannot. If you switch medications, you may need a washout period (a stretch of several weeks of taking no drugs) in order to prevent dangerous interactions between a new drug and the lingering effects of the previous one. Choosing a Medication One day it may be possible to use biological markers and other indicators to predict exactly which antidepressant will work best for each person. Right now, though, psychiatrists and doctors who prescribe antidepressants choose a particular drug and dosage based on many factors.

Diagnosis. Certain drugs work better for specific symptoms and types of depression. For example, some antidepressants may be better when insomnia is an issue. The severity of your illness or the presence of anxiety, obsessions, or compulsions may also dictate the choice of one drug over another.

Age. As you age, your body tends to break down drugs more slowly. Thus, older patients may need a lower dosage. For children, only a few medications have been studied carefully.

Health. If you have certain health problems, it’s best to avoid certain drugs. For this reason, it’s important to discuss medical problems with a primary care doctor or psychiatrist before starting an antidepressant.

Medications, supplements, and diet. When combined with certain drugs or substances, antidepressants may not work as well, or they may have worrisome or dangerous side effects. For example, taking SSRIs with another type of antidepressant known as monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) can be fatal. Combining the herbal remedy St. John’s wort with an SSRI or an MAOI could lead to serious side effects, because this herb boosts serotonin. Likewise, mixing St. John’s wort with other drugs �?including certain drugs to control HIV infection, cancer medications, and birth control pills �?might lower their effectiveness. Eating certain foods, such as cheeses and pickles, while taking an MAOI can raise your blood pressure to dangerously high levels.

Alcohol or drugs. Alcohol and other substances can cause depression and make antidepressants less effective. Doctors often treat alcohol or drug addiction first if they believe either is causing the depression. In many instances, simultaneous treatment for addiction and depression is warranted.

Mental health and medication history. Depending on the nature and course of your depression (for example, if your depression is long-lasting or difficult to treat), you may need a higher dosage or a combination of drugs. This may also be true if an antidepressant has stopped working for you, which may occur naturally or after you’ve stopped and restarted treatment with it. Types of Psychotherapy Depression can bring everything in your life �?work, relationships, school, and even the most minor tasks �?to a grinding halt, or, at the very least, gum up the works. The aim of psychotherapy is to relieve you of symptoms and to help you manage your problems better and live the healthiest, most satisfying life you can.

Some evidence suggests that by encouraging more constructive ways of thinking and acting, psychotherapy makes future bouts of depression less likely. Three schools of psychotherapy �?cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, and psychodynamic therapy �?play a primary role in combating depression.

Which type of psychotherapy works best? There’s no simple answer. Just as people respond differently to different drugs, you might do better with one type of therapy than with another. Many people find that a blended approach �?one that draws on elements of different schools of psychotherapy �?suits them best. Cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy aims to correct ingrained patterns of negative thoughts and behaviors. To accomplish this, you are taught to recognize distorted, self-critical thoughts, such as "I always screw up"; "People don’t like me"; "It’s all my fault." During cognitive behavioral therapy, your therapist may ask you to judge the truth behind these statements, to work to transform such automatic thoughts, and to recognize events that are beyond your control.

Along with cutting down on the number of negative thoughts, cognitive behavioral therapy also focuses on breaking jobs into smaller, more manageable pieces that set you up for success. You rehearse new ways of coping with problems and practice social skills that can help wean you from actions that provide a fertile breeding ground for depression, such as isolating yourself. Your therapist may assign you tasks to reinforce your learning. For example, you might keep a log of thoughts that occur as you try out your new skills. As negative patterns become clearer, you can learn to redirect them. Interpersonal psychotherapy

Interpersonal psychotherapy concentrates on the thornier aspects of your current relationships, both at work and at home. Weekly sessions over three or four months will help you identify and practice ways to cope with recurring conflicts. Typically, therapy centers on one of four specific problems: - grief over a recent loss

- conflicts about roles and social expectations

- the effect of a major change, such as divorce or a new job

- social isolation.

Psychodynamic therapy

Psychodynamic therapy focuses on how life events, desires, and past and current relationships affect your feelings and the choices you make. In this type of therapy, you and your therapist identify the compromises you’ve made to defend yourself against painful thoughts or emotions, sometimes without even knowing it. For example, someone with an overbearing parent may unconsciously find it difficult to risk developing intimate relationships, out of fear that all close relationships will involve a domineering partner. By becoming aware of links like this, you may find it easier to overcome such obstacles.

You and your therapist may talk about disruptions in your early life �?perhaps the death of a parent, your parents�?divorce, or other disappointments �?to determine their effect on you. While the duration of psychodynamic therapy can be open-ended, a variation called brief dynamic therapy is limited to a specific amount of time (generally 12�?0 weeks). It applies a similar lens to a specific emotional problem. Not just for individuals

Group, family, or couples therapy may also be part of a plan for treating depression or bipolar disorder. Group therapy draws on support generated from people in the group and uses the dynamics among them, along with the leader’s help, to explore shared problems. Family therapy and couples therapy also delve into human interactions. Like group therapy, the aim is to define destructive patterns �?such as scapegoating one family member or enabling a spouse’s alcohol abuse �?and replace them with healthier ones. These therapies can uncover hidden issues and establish lines of communication. Family therapy is especially useful when one person is struggling with emotions that spill over into the family. The Ingredients of Good Therapy There are many different approaches to psychotherapy, but all good therapy shares some common elements. To start with, make sure that your therapist has a state license. While psychotherapy isn’t always comfortable, you should feel reasonably at ease with your therapist. In the best case, the two of you will be, or will become, a good match. Of course, both of you must respect ethical and professional boundaries. It’s important that therapy provide some relief. Your therapist should not only offer reassurance and support, but also suggest a clear plan for how the therapy will proceed. You and your therapist should agree upon realistic goals for the therapy early on. While well-defined problems might be addressed relatively quickly, you may need to approach more difficult problems from many angles, which will take longer. Since mood disorders can have a broad influence on relationships, work, school, and leisure activities, therapy should address these areas when �?or if possible before �?they become a problem. Therapy isn’t just for uncovering painful thoughts, although that’s part of the work. Good therapy also addresses how you can adjust, adapt, or function better. And it helps you understand the nature of your distress. You should feel that your therapist approaches the important issues in your life in a way that’s unique to your needs, not from a one-size-fits-all perspective. Pertinent issues springing from your culture, sex, and age, as well as individual differences, should shape the direction therapy takes. If a doctor other than your therapist prescribes antidepressants for you, the two should communicate. If they don’t do so on their own, you may want to encourage collaboration by asking your therapist and doctor to speak regularly. Your therapist ought to understand the medication portion of your treatment, encourage you to take medications as prescribed, and help monitor your response.

Although it’s not uncommon to feel stuck at times, don’t persist for months with that feeling. Some difficult problems take a long time to unravel, but you should sense progress. If you don’t, it’s a sign that the match between you and either the technique or the therapist isn’t right. If four to six months have gone by and you don’t feel better, it’s a good idea to consult another therapist. 10 Questions to Ask When Choosing a Therapist Whether you get a recommendation for a therapist from your primary care doctor, a friend, or your insurance company, finding out about his or her background and training can help you feel comfortable with your choice. Here are some questions to ask before settling on a therapist: - What’s your training (i.e., what certification or degrees do you hold)?

- How long have you worked in this field?

- What kinds of treatment or therapy do you think might help me?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of the different approaches, including medication?

- How does the treatment work?

- What are the chances that treatment will work?

- How soon should I start feeling better?

- How will we assess my progress?

- What should I do if I don’t feel better?

- How much will treatment cost?

It’s hard for a therapist to give precise answers to some of these questions, because no single therapist or type of treatment is best for everyone. But there are some general responses you should be looking for. The therapist should have formal training and certification, or be on the way to getting it. There’s a tendency for mental health professionals to offer the particular type of psychotherapy that they do best. It’s good if the person can describe the merits and drawbacks of different types of treatment, including ones they don’t do. The therapist should also let you know how he or she will monitor your progress. If you don’t feel there’s been improvement after several months, consider getting a second opinion. Electroconvulsive Therapy Reality often fails to jibe with movies and books. While psychotherapy and antidepressants have garnered some positive fictional portrayals, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) typically evokes only frightening pictures. More than 30 years after One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest won its Academy Awards, the images from the film linger in many people’s minds. Yet ECT remains one of the most effective treatments for severe depression, with response rates of 80%�?0% for people with major depression. ECT may also be used to treat mania when a person fails to respond to other treatments.

Despite its effectiveness, doctors usually reserve ECT for situations in which several drugs have failed. That’s partly because of its technical complexity, and partly because of its negative image. How ECT works

The discomfort of ECT is roughly equivalent to that of a minor surgical procedure. The purpose of ECT is to induce a seizure, which acts as the therapeutic agent. Before receiving treatment, a person is given general anesthesia. Then the doctor places electrodes on the patient’s scalp and administers an electric current in a brief pulse that causes a seizure. Medicine is given to prevent the muscular effects of the seizure, so there are no obvious convulsions. The seizure is evident only because it registers on an electroencephalographic monitor. The procedure takes a few minutes, after which the person is roused from the anesthesia.

On average, 6�?2 treatments are given over several weeks. Contrary to what some people might expect, when there is a good response, the improvement occurs gradually over the course of treatment, rather than all at once. Generally, the response occurs faster than with medications, making ECT a good treatment for severely depressed people who may be at very high risk for suicide.

In the best-case scenario, a prospective patient is well-educated about ECT. Usually, doctors and nurses explain the treatment in detail, and often patients watch videotapes of the procedure. Sometimes other people who have had ECT explain what the experience is like to further demystify it. Patients decide if they want to try ECT only after they have been fully informed about how the procedure works and what its risks and benefits are. Most states have clear safeguards against involuntary ECT treatment. ECT and memory

The most commonly discussed side effect of ECT is memory loss. Routinely, patients lose memories of events that occurred just before and soon after treatment. After the treatment concludes, some people will have difficulty remembering things that occurred during the course of treatment. Once all the treatments have ended, relatively few people have persistent memory problems. However, ECT may exaggerate problems in people already having memory trouble.

Other side effects are also fleeting. Some people feel a bit sedated or tired on the day of the procedure, or they might have a mild headache or nausea. However, these symptoms might come from the anesthesia rather than ECT itself. To date, no study has shown that ECT causes brain damage.

One drawback to ECT is a relapse rate of about 50% in people treated for severe depression. It may be even higher with so-called double depression (the combination of depression and dysthymia). To help avoid a relapse, a person who responds to ECT might also take an antidepressant medication or mood stabilizer. If dual treatment doesn’t work, some people receive maintenance ECT on an outpatient basis about once a month. Some people with severe depression have done very well with this approach.

|

|

Reply

| |

New Approaches to Treatment Two newer treatments are geared toward people who haven’t responded well to other, more traditional approaches. While they are somewhat similar to ECT, in that they rely on delivering impulses (electrical or magnetic) to achieve results, neither has the proven track record of ECT. Vagus nerve stimulation

In the summer of 2005, the FDA approved a device known as a vagus-nerve stimulator as a treatment for adults with depression who haven’t responded to four or more other therapies. Extending from the brain through the chest cavity, the vagus nerve helps control your breathing and is linked to the amygdala, hypothalamus, and other parts of the brain that modulate mood and anxiety. A vagus-nerve stimulator is a surgically implanted device similar to a pacemaker that delivers a small electrical impulse to this nerve for about 30 seconds every five minutes. Although vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) was initially developed as a method for controlling epilepsy, researchers found that it improved mood in some people.

The FDA based its approval on research showing that VNS was safe and effective. One study cited in the FDA approval documents showed that 31% of people getting VNS responded well to the treatment in the first 12 weeks of therapy and 45% did after one year. The most common side effects are cough and neck pain. Many people also find that their voice often becomes hoarse while the stimulator is delivering its impulse. Between impulses, though, the person’s voice returns to normal.

Although the VNS device is on the market, VNS is a relatively untested treatment that has not yet been proved effective by randomized, controlled trials. For this reason, the consumer group Public Citizen petitioned the FDA not to approve it. The FDA has mandated that Cyberonics, the company that makes the device, conduct studies to monitor its effectiveness. For the most part, this treatment should be reserved for exceptional cases where many other therapies have been tried without success. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS)

Another treatment for people whose depression has not responded to traditional therapy, called repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), is also being tested in several centers. During rTMS, a donut-shaped wand passed along the surface of the scalp focuses magnetic pulses on a small part of the brain. This technique isn’t invasive and doesn’t cause seizures or require anesthesia, as ECT does. A person undergoing rTMS can sit comfortably in a chair and remain awake during the whole procedure, which takes 30�?5 minutes. Usually, it is done once a day for 10 days.

Although results in trials are still inconsistent, the news from what now amounts to a large number of controlled studies is getting better. For example, in one study, using rTMS at different frequencies on different areas of the brain improved depression in people who had not responded to drugs. Researchers have also found weekly rTMS helpful to adults with bipolar disorder who are taking lithium. Overcoming Barriers to Treatment  In a perfect world, every treatment would be right on the mark, every doctor or therapist would earn his or her patient’s confidence, and people would find it easy to follow each bit of helpful advice. Clearly, this isn’t the reality. So what are some of the barriers to getting good treatment and sticking with it? And how can you surmount them? The health care system

Navigating the health care system isn’t always easy. Some health insurance companies confine your choices to a narrow panel of doctors or therapists. Or there may be relatively few mental health professionals in your area. It may also be hard to advocate for yourself, especially when you’re depressed. Perhaps a supportive family member can help you deal with your insurance plan or accompany you to an appointment.

Most private insurers, Medicare, and managed-care plans provide some coverage for mental health treatments. However, copayments may be higher than for other types of care. There may also be a limit on how many visits the company will cover. Calling your insurer is the best way to figure out your out-of-pocket cost.

If a psychiatrist or doctor is prescribing your medication and another person is conducting psychotherapy, it may be difficult to coordinate the different aspects of your care. Let both people know that it is important to you that they talk with each other.

It’s also important that you do all you can to understand your treatment. Bringing a pad and paper to your appointment and taking notes may help you take in information that is sometimes confusing. For example, studies show that although doctors report telling patients about side effects, many patients don’t remember hearing that information. Also, make sure you bring up any important and possibly time-consuming issues at the beginning of your appointment. Appointment time is often limited, so plan to make good use of the time, and make follow-up appointments when necessary. Finding the best treatment