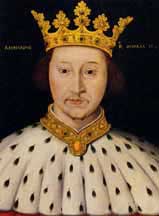

| | ROOTS OF THE CONFLICT: First Act | |  RICHARD II | From the nine-year-old boy king who lost his shoe as he was carried in exhaustion from his coronation�?.to the thirty-three year old deposed monarch who died under mysterious circumstances at Pontefract�?.the action (other than the begetting) in the drama of the Wars of the Roses begins in the reign of Richard II. This brave little king who faced down an angry mob of revolting peasants at Smithfield had chafed under the restrictions of his prolonged regency period. A coterie of barons dominated the government and were loath to relinquish an iota of their power even as the young king grew and matured. It was not until Richard’s marriage to Anne of Bohemia in 1382 that things began to change. With little hands-on experience, he began to assert his independence from his councilors. He gathered about himself a new court party, headed by Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford, and Michael de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk. He had a bitter quarrel with John of Gaunt, his uncle, while on an expedition to Scotland in 1385. The following year, however, when Gaunt went to Spain to marry Constance of Castile, Richard found himself at the mercy of a resentful baronial party led by another of his uncles, Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, he of the aforementioned choleric disposition. In the so-called Wonderful Parliament (1386) that group forced the king to dismiss Pole from the chancellorship and imposed on him a new baronial council. Richard did not submit for long. He obtained a statement from the royal judges declaring the proceedings of the Parliament to have infringed his kingly prerogative and raised an army in northern England. However, his supporters were defeated in battle at Radcot Bridge (1387), and the king, threatened with deposition, had to submit to the proceedings of the Merciless Parliament of 1388.

His friends, Pole, de Vere, and others, were accused of treason by five lords appellant—Gloucester; Richard FitzAlan, Earl of Arundel; Thomas de Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick; Thomas Mowbray, Earl of Nottingham and later 1st Duke of Norfolk; and the Earl of Bolingbroke (later Henry IV)—and those that did not escape the country were executed. It is said that Queen Anne went down on her knees in front of the self-styled Lords Appellant to plead for the life of Sir Simon Burley, Richard’s old tutor, and was denied. The Lords Appellant ruled the country until 1389, when Richard quietly reasserted his authority. Aided by Gaunt, who had returned from Spain, Richard ruled in comparative peace for the next seven years. After Anne’s death in 1394, he went to Ireland to settle troubles there, and in 1396 married a seven-year-old French princess, Isabella, to obtain a truce in the war with France. In 1397, Richard suddenly took his revenge on the Lords Appellant: Gloucester, Arundel, and Warwick were themselves accused of treason and respectively murdered, executed, and banished; the following year, Norfolk and Bolingbroke, now Duke of Hereford, too were banished after a mysterious quarrel between them. The king became increasingly despotic in his methods of government, strengthening his personal army, imposing heavy taxes and fines, and possibly even planning to supersede Parliament. On the death of John of Gaunt in 1399, he confiscated the Lancastrian estates, to which the exiled Duke of Hereford was heir, practically daring retribution. While Richard was on another expedition in Ireland, Hereford landed in England and rapidly gathered support. Richard hurriedly returned, but his cause was lost. He was forced to abdicate on September 29, 1399. As Richard was childless, the next in line to the throne was Edmund Mortimer, the eight-year-old Earl of March, a descendent of Lionel of Antwerp, whom as we know was the older brother of John of Gaunt, Henry’s father. However, Parliament declared that Hereford could succeed to the throne, as the last thing that was wanted was another protracted regency. Richard was imprisoned in Pontefract Castle and there died, very possibly murdered, February 14, 1400. And thus concludes the Lancastrians' opening sally of this conflict.

|

Free Forum Hosting

Free Forum Hosting