|

It was the Tudors who made the Tower of London notorious as a prison. Prisoners were expected to pay the costs of their upkeep. If they didn't have the funds, they would have to depend upon the charity of family and friends on the outside. Once a prisoner was convicted of treason, all his property was confiscated by the Crown and he would be maintained out of the proceeds. He was entitled to an allowance for food, fuel, and light according to a fixed scale which varied according to his rank. Prisoners of rank were often allowed to have their own servants with them. Some prisoners had the "liberty of the Tower" which meant they could move freely within the Tower walls during the daytime. "Close Prisoners" were restricted to their cells, not allowed to have visitors, write or receive letters, and were always under the watchful eye of their warder. A prisoner could be held indefinitely simply at the monarch's pleasure. Only a minority of prisoners were executed. Of the rest, some were freed, some were released on surety from family or friends, some were sent away to live under surveillance, some were banished, some were transferred to other prisons, and some died in the Tower of natural causes. The Earl of Courtenay, that last surviving sprig of the White Rose, spent most of his life behind the Tower’s thick walls, released in the reign of Mary I. Executions took place only following condemnation by the legal process, usually after a trial or act of parliament. The full penalties for treason were hanging, drawing and quartering, usually at Tyburn. For prisoners of rank, death was by beheading with an axe, almost always on Tower Hill. Imprisonment in the Tower and execution on Tower Hill were a recognition of rank.

The most famous Tower prisoners were Edward V and his brother Richard, Duke of York, who disappeared into the Bloody Tower shortly before Henry Tudor’s victory at Bosworth Field and were never seen again, starring at the center of one of history’s greatest unsolved mysteries. Did Richard III, who had usurped young Edward’s throne, have the boys discreetly put to death, or was it by order of Henry VII? This vanishing act of the Yorkist heirs served to plague the new Tudor dynasty with a rash of pretenders to the throne. Allegedly the Duke of York, Perkin Warbeck was imprisoned in the Tower and subsequently executed. Edward, Earl of Warwick, another Yorkist heir, also spent most of his life in the Tower, only to be executed there on a flimsy pretext. Henry VIIs financial advisors, Edmund Dudley and Richard Empson, were clapped in the Tower upon Henry VIIIs accession to the throne on charges of financial mismanagement. It was a popular imprisonment, as Dudley and Empson were convenient scapegoats for Henry VIIs policies. However, Dudley pushed his luck with both an escape attempt and a plotted uprising, and met the axeman on Tower Hill in 1510. The first important Tudor prisoners of Henry VIIIs reign were Sir Thomas More and Bishop Fisher of Rochester, both of whom were executed in 1535 for refusing to acknowledge Henry VIII as Supreme Head of the English Church. Anne Boleyn, for her coronation in 1533, arrived at the Tower in a river procession from Greenwich, just as Henry's mother, Elizabeth of York, had done years before. Henry was at the Tower to greet Anne upon her arrival. That evening there was a great banquet in the White Tower, with music, fireworks and salvos from the Tower guns. A mere three years later she would return with far less fanfare as Henry’s prisoner, to stand trial for treason and adultery. She was lodged for 18 days in her coronation apartments in the Queen’s House before her execution on Tower Green.

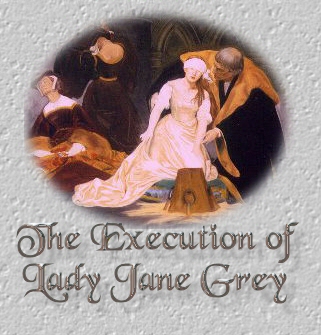

The judicial murder of an anointed queen seemed to pave the way for Henry VIII to lop off the heads of other women during his reign. Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, former governess to his elder daughter Mary, was nearly 70 when Henry had her executed on Tower Green in 1541. Catherine Howard, another of Henry’s wives and a cousin to Anne Boleyn, was executed there for adultery in 1542. Jane, Viscountess Rochford, followed Catherine to the block the same day, ostensibly for aiding and abetting the queen’s love affair with Thomas Culpeper. George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford and Jane’s husband, met his end on Tower Hill in 1536, along with Sir Henry Norreys, Sir William Brereton, Francis Weston, and Mark Smeaton, all alleged paramours of Anne Boleyn. Catherine Howard’s gentlemen friends fared no better in 1542; Thomas Culpeper and Francis Dereham were also executed there. July 1540 saw the execution of Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex and former chief minister of the King. As Henry’s chancellor, he had modernized the Tower's defenses and, ironically enough, sent many others to their deaths on the same spot. The last of Henry’s noble victims was Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, executed shortly before the king’s death in January 1547. Surrey’s father, Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk and uncle of the two decapitated queens, was saved from a similar fate only by Henry’s timely demise. The reign of Edward VI saw a continuation of the Tudors�?political executions. Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, Edward’s Lord Protector and maternal uncle, met his death at the Tower in 1552, accused of treason. Ironically, Somerset had ordered the execution of his brother, Thomas Seymour, Baron Sudeley and Lord High Admiral of England as well as husband to Henry’s last queen, Catherine Parr, just four years prior. At Edward’s early death, John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, fancied himself a kingmaker and attempted to bypass the Act of Succession’s provisions for Mary and Elizabeth by putting his daughter-in-law, Lady Jane Grey, on the throne. Northumberland, like his father, got the axe and Jane a room in the Beauchamp Tower when Mary seized her throne back from his clutches, and his sons, most notably Robert Dudley, future Earl of Leicester and favorite of Elizabeth I, were imprisoned in the Tower. Following Wyatt’s Rebellion in 1554, Jane’s father, Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk, was executed for his part in the proceedings; Jane and her husband Guildford Dudley soon followed him to the block.

Elizabeth, suspected of complicity with Wyatt, was packed off to the Bell Tower by her sister. Like her mother before her, Elizabeth was brought to the Tower by water and entered at Traitor’s Gate. At first Elizabeth refused to land. Then, she protested her innocence saying, "I come in no traitor but as true a woman to the Queen's Majesty as any is now living." Elizabeth was allowed out every day to exercise but she was allowed no other visitors except a doctor. She was permitted no books. She was questioned repeatedly, but after two months without incriminating herself, she was removed to Woodstock.

In March 1554, Mary came to the Chapel of St. John in the White Tower to be married by proxy to Philip of Spain. The actual wedding was four months later at Winchester Cathedral. When Mary restored the pope's supremacy, religious opposition became a crime punishable by the state. After the heretic had been condemned by the church, he was handed over to the state for execution. This was the fate of Thomas Cranmer, Henry VIIIs Archbishop of Canterbury, and many others. Most heretics were burned alive at Smithfield, located outside the Tower walls to the northwest.

Elizabeth I spent much of her reign warding off the threat from Catholic Europe. Jesuit priests, who were often tortured, were lodged in the Salt Tower. Noble recusants (people who refused to attend Church of England services) and others who might have opposed her rule were locked up. Never had the Tower been so full of prisoners, or such illustrious ones: bishops, archbishops, knights, barons, earls, and dukes all spent months, some of them years, languishing in the towers of the Tower of London.

Elizabeth’s heir-presumptive, Catherine Grey, sister to the unfortunate Jane, found herself in Elizabeth’s former Bell Tower prison when it was revealed in 1562 that she was not only pregnant, but secretly married to Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford. Catherine was supposed to be kept a “Close Prisoner�? but her enterprising spouse, also in the Tower, managed to get in to see her and impregnate her again, much to Elizabeth’s fury. Eventually Catherine was paroled into the keeping of her paternal uncle, remaining under house arrest until her early death of consumption in 1568. Meanwhile, her younger sister Mary had also angered the queen with a clandestine marriage in 1565 to a royal gatekeeper, Thomas Keyes, and was arrested as well.

One of Elizabeth’s favorites, Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, son of her rival Lettice Knollys, devastated the aging queen with his rebellion and was executed on Tower Hill in 1601. The Devereux Tower is named for him.

Go HERE for a virtual tour of the Tower of London BACKGROUNDS © ForeverAmber ©2005 ALL MY TUDORS |

Free Forum Hosting

Free Forum Hosting